Talking about race can be challenging. Talking about race to your kids can be especially challenging. Talking to your kids about race when they racially identify differently than you, can definitely be challenging. Hopefully this article can help!

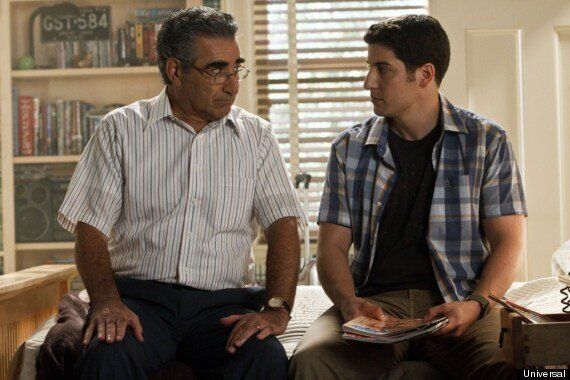

We are all familiar with the dreaded, awkward conversations our parents had with us about the “birds and the bees”. Even if your parents avoided the conversation at all costs, if you’re a millennial or older then you can at least recall Eugene Levy having this conversation in the cult classic “American Pie” (For a comedy refresher, clip is linked here but note NSFW) My parents were a bit unconventional in their approach about that conversation—as many of my classmates can attest to—but that’s a conversation for another day.

We’re here to talk about race! And if you’re (also) struggling with the best way to have these conversations with your kiddos or what to talk about here are some tips that I think can help. The tips shared here are inspired by my recent research and the research titled “Racial Socialization of Biracial Youth: Maternal Messages and Approaches to address Discrimination” (Rollins and Hunter, 2013) published in the peer-reviewed academic journal “Family Relations” in 2013.

- Talking and Learning about Race is not a ONE-time conversation

Recently I was a guest lecturer for a college course on race and when I asked the freshmen students if they can remember their parents talking to them about race. I was very surprised that only 3 out of 20 diverse mix of students raised their hands. The wild thing is— WE ALL COMMUNICATE ABOUT RACE, ALL THE TIME—but we’re likely not intentional or even conscious about when we do.

“Open communication fosters racial awareness, reduces inconsistent messages, minimizes ambiguity, increases familial interaction, buffers youth from stereotype threat effects and decreases the effects of conflicting messages about race.”

-Rollins & Hunter, 2013, p.141

Think about it- who was the first person to talk to you directly about race and society’s views on race? For many people, these conversations start at grade school with their peers. And for many biracial people and people of color (myself included) an encounter with racism at school sticks out as a defining moment for them that taught them what race means.

Race is one of those things that has meaning (although it shouldn’t) that gets learned little by little over time. What starts as a preschooler asking “why is my skin like chocolate milk and my mommy’s skin isn’t?” can change into “my friends say I don’t fit in with their lunch table anymore” to “Johnny was allowed to register for AP math & I wasn’t even though I scored higher than him on the tests.” The conversations that your kids are having at school may not directly talk about race, but research shows that race is often a factor in the statements mentioned above.

Since kids are total sponges, they are constantly seeking to understand their world and their place in it especially when it comes to their peers at school. “What do you mean, pre-teens obsess about their friends? Never!” All kidding aside, recognizing that your kids are constantly learning new things about what race means in the U.S. is an important first step! But that’s not all, you still need to talk to them about it.

And the benefits of talking about it are impactful. Rollins research notes, “Open communication fosters racial awareness, reduces inconsistent messages, minimizes ambiguity, increases familial interaction, buffers youth from stereotype threat effects and decreases the effects of conflicting messages about race.”

2. Reinforce Family & Cultural Pride

An easy place to start to talk about race is to start with yourself and your family. Talk about your own cultural pride and help your child develop pride in their own ethnic and cultural identity too- even if theirs is different from yours. Rollins and Hunter cite this as “promotive messaging” which is described as strengthening the child’s sense of self, believing in one’s ability, and passing on cultural traditions and values.

My parents are as white bread as they come but they were awesome about intentionally connecting me with African American culture as best as they could. Some of their cultural educational efforts looked like parades, books and dragging me to panel discussions on race at the local college when I was 10. Yep, I was 10. Other times, my parents tried to connect me with other Black families with daughters or other families with biracial daughters and one time even flat out asked, “can my daughter go to (your black) church with you sometime?” I also remember my mom taking me to see Alvin Ailey (all black) American Dance company perform–on a school night!

My parents are as white bread as they come but they were awesome about intentionally connecting me with African American culture as best as they could. Some of their cultural educational efforts looked like parades, books and dragging me to panel discussions on race at the local college when I was 10. Yep, I was 10. Other times, my parents tried to connect me with other Black families with daughters or other families with biracial daughters and one time even flat out asked, “can my daughter go to (your black) church with you sometime?” I also remember my mom taking me to see Alvin Ailey (all black) American Dance company perform–on a school night!

Even though I didn’t always understand why they were doing this for me at the time, I remember feeling loved by their intentional effort and feeling excited to see examples of others like myself and being connected to them.

3. Proactively Prepare Kids for the Tough Stuff Too

While the dance performances and cultural festivals can be fun, the research also suggests that it is just as important to prepare children for potential bias and discrimination proactively. Rollins & Hunter describe this kind of messaging as “protective” and can be included with promotive messaging.

“Combining messages that prepare youth for racism and discrimination with education, awareness, and racial pride better equips youth to negotiate their minority status.”

Rollins & Hunter, 2013, p. 149

“Combining messages that prepare youth for racism and discrimination with education, awareness, and racial pride better equips youth to negotiate their minority status.”

These conversations and harsh realities can be especially challenging because no parent wants to think of their child experiencing these kinds of painful events. However, I encourage you to push through the knot in your throat because if you do talk to them about it proactively that preparation can be empowering. Several of the biracial participants in my research shared that their parents didn’t talk about race, but all of them had experienced racism.

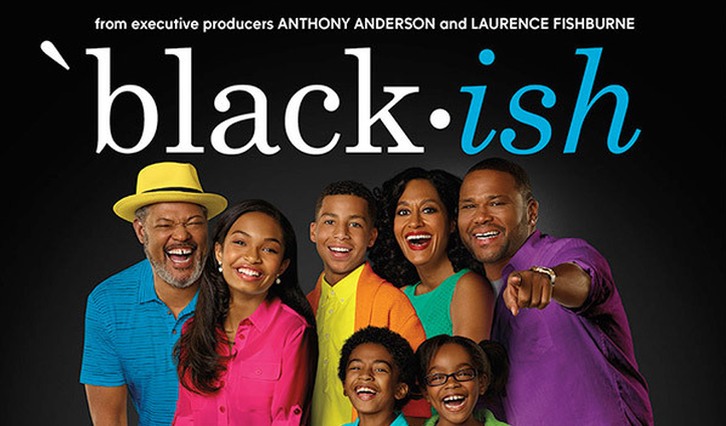

If you need some extra help having these conversations or struggle relating because you might identify differently than your child, consider the following. Books are often great conversation starters for little people too. We have lots of conversations with our boys around reading time with books featuring black and diverse children. Here’s a quick list from another professional focused on early-childhood learning.

Besides books you can also seek to form relationships with other families that may share the same ethnic heritage as your child and who can speak about discrimination from personal experience. One my research participants who is biracial (Black/Mexican) and grew up predominately with her Mexican-American family, told me that it was her Black neighbors who would talk to her about what it meant to “be Black” and she found it helpful.

My parents would also use movies and have family discussions around tough issues. Like, we watched the movie Roots in its entirety as a family. Between segments my dad would pause the TV and ask my (white) brothers and I what we thought about what we were watching. This and moments like it, reinforced family values about right and wrong and led to quality bonding time as a family.

4. Acknowledge the Differences

Whether you feel qualified to have these conversations with your child or not (and honestly do we ever truly feel qualified as parents about anything?) you don’t have to worry. It’s not about being the expert, it’s about being their parent and showing that you care.

You can take the pressure off by acknowledging the differences—and the likenesses—between you and your child. The reality is whether you talk about it or not, your child will pick up on the differences anyway. They may even obsess over them. And we certainly don’t want them to do that for the wrong reasons. Make sure you’re a part of the conversation and use these moments as opportunities to affirm them for their unique qualities.

Also acknowledging the differences between your experiences gives permission to be honest and vulnerable with each other. By teenage years kids learn parents don’t have all the answers anyway so when you connect with them around that, I believe it can create a safe space for them to be vulnerable with you too.

5. Ask for Their Opinions

In fact, in these safe spaces of communication I believe you can meaningfully connect by also asking for their opinions. Ask them how they feel about what you read together, what do they think about what is going on in the world (if they’re aware of racial issues in the media), what do they think can make it better in your community? Not only will this give you insight into what they’re experiencing emotionally and socially but these conversations will empower them to translate these thoughts/feelings into positive action.

Comment and let us know your thoughts on these tips and if you have others!